On my hard drive, at the time of this writing, I have several files of novels, scripts, ideas, and treatments, all in varied states of (in)completion. I have them tucked away in a folder that is not clicked on often for reasons that are immediately obvious. I have yet to meet anyone who readily wallows in his, or her, unfinished failures. Perhaps I haven’t met enough people, though.

The reality of my situation is that these many projects will never see the light of day in any form, no matter how hard I try to convince myself otherwise. Sure, maybe my failed novel The Genius of Professor Clay could be adapted for the screen, but that still doesn’t change the fact that the damn thing isn’t finished. And really, how would an adaptation help the fact that the main character’s motivations are at best confusing, and at worst unlikable and criminal. Maybe the indie circuit could take a shine to it, I suppose, but what studio would want to back a screenplay that would only appeal to the most miniscule of niche audiences? To the folder of failure, it goes.

Now, Errand Men on the other hand, that could have potential. It was originally supposed to be a graphic novel, detailing the lives of two hired grunts who work for underground mafioso and gangsters, and since it’s already in script format, it should be a breeze to adapt. Hell, the characters are even likable, in that quasi-Quentin Tarantino kind of way; where despite the characters are participating in illegal activities, we are able to like them because they say funny things about the minutia of popular culture. But, there’s still that niggling, taunting fact that the script remains unfinished. Besides, the material is too derivative and reliant on tired, 90’s cinema cliches.

But of all the failures that I have yet to finish, the one that seems to dog at my figurative heels and never seems to let itself go is Normandie. It was intended to be, at first, a mini-series of comic books, and took place the few days before and during the riots in L.A in 1992. I had spent countless hours of research on the history and the geography of the city at the time, I had written up detailed character sheets for my artist to work from, and I even went so far as to summarize the entire plot, and detail what was to happen over the entire arc of the story, so there was no way that I couldn’t finish it.

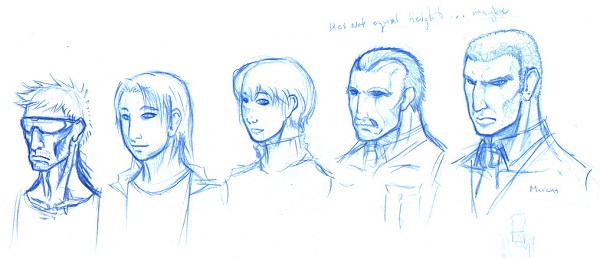

Above is the very first profile shots of what would have been the main characters of Normandie. From left to right, we have Pete, Matthew, Laurel, Declan, and Marcus.

Then, the bottom fell out.

I began to realize, as I was starting to write the very first page of the script, that the characters, again, proved to be problematic. Its not that they were unlikable, or that the reader couldn’t relate to them, its that there were too many of them. The story was all over the place as it is, and having five main characters share the spotlight would dim the focus of this magnificent story that had to be told, goddammit. Sacrifices had to be made.

So out went Laurel, the rogue vigilante with cat-like reflexes and a killer instinct. But then, I figured that the cast was too male-dominated, and I would need to appease the throngs of female comic book readers that apparently exist and take one of the male characters and give him a sex-change. Since I already knew what Laurel was going to look like, anyway, I decided to replace the drug-addled Pete with Laurel, deciding to give her his original character, and see how it would work out. It worked out well.

It’s a shame that Pete never made it into the story, because I truly loved the character design.

Now, we had a varied cast, perfectly reflecting the racial tension that permeated the setting: Marcus, the black actuary who views the growing hostility and possible violent outbreak as an inevitability; Matthew, the teenage white boy who suffers from Williams’ Syndrome, and sees the world through the naive and precocious eyes of a mentally disabled child (instant pathos and Eisner award material to be sure); Laurel, the down on her luck druggie who had the world ahead of her, but succumbed to the dangerous world of heroin addiction; and Declan, a veteran corrections officer at Norco prison who has a front row seat to the looming danger of…

…wait, Declan?! What’s an Irishman doing in L.A?

No, that won’t do at all. Not in the slightest. He has to be Latino, or at least Mexican. So I dropped Declan and substituted Sergio Alvarez in his place. Yes, that way, a racial parallel can be drawn between those who guard, and those who serve.

Did I say Eisner Award earlier? Fuck that; I want to be the first guy to win the Pulitzer Prize for writing a comic book. Alan Moore who?

So, with the outline written, the character concepts drawn, and my artist ready and willing, I quickly set to scripting the very first chapter, and that’s when it hit me: what are these characters doing with super powers?

I forgot to mention this until now, but all of the characters that I had listed had some sort of special power. Marcus had visions of the future, Laurel (Pete) could grow poisonous needles from his/her skin, the original Laurel had hyper-fast reflexes, Matthew had the power of healing, and Declan/Sergio was physically invulnerable and inhumanly strong. They were all granted powers by a cosmic force that humanity had come to known as Fate. Fate, at one time during each of the character’s lives, had anointed them powers that reflected the lives they were leading, each character’s power having a purpose that would play itself out during the course of events during the story.

Yes, I am completely serious.

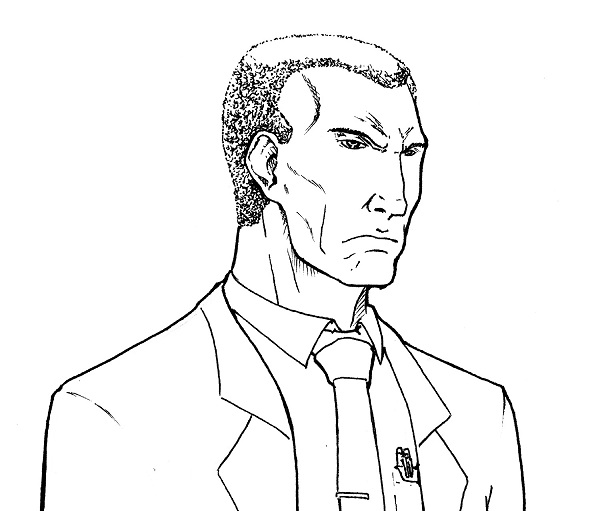

I’m as serious as Marcus is in this profile shot. His character design was never fully realized, and I always felt like this shot made him look too old.

My thinking was, at the time, that since this was meant for a comic book, that it needed to have an element of high fantasy. Superhero powers influencing the very real L.A race riots, how could it get any higher than that?

It could have ended there, as I stuffed whatever I managed to save into my Folder of Empty Promises, but it did not. Some months later, maybe a year, I was feeling nostalgically depressed, and succumbed to my self-destructive urge to look at my pages upon pages of wasted potential. When I looked at my Noramandie file, a sudden flicker of inspiration took a hold of me. Normandie failed because the concept of powers, Fate, and whatever diminished the gravitas and solemnity of the setting. So, what if I removed all of that, and made it into an historical-fiction novel? I would focus on the characters and their relationships, providing a rich background for this soon-to-be riot to take place. Thus, when the riot inevitably hit, it would be all the more interesting and thrilling because the characters that we have come to know and care for are involved.

This literally could not fail.

And off I went, scrapping together whatever plot outlines I could gather and re-formatting them to fit a novel’s structure. The character concepts were indispensable to me, as they reminded me of what I had planned back when Normandie was supposed to be a comic book. Removing the powers and the element of Fate was easier than I had anticipated, leaving a perfect, blank canvas for me to work with.

Over the course of a month, I had started several chapters, each one devoting itself towards one of the main characters. Marcus’ chapters, I felt, would be the cornerstone of the entire narrative. If there was such a thing as a main character in Normandie, it would be Marcus. Oddly enough, his chapters weren’t the hardest to write, as that designation went to Matthew’s. I found it draining, trying to write his dialogue and exchanges with other characters without devolving into saccharine mush and schmaltz. Characters with mental disabilities walk a fine edge, teetering between emotionally manipulative and failed sentimentality. I’d like to think that I portrayed Matthew as believable as possible, while still maintaining that air of empathy that people naturally have towards people with disabilities.

Of all the chapters, though, I enjoyed writing Sergio’s and Laurel’s the most. With Sergio, I had him have a devoted wife, Maria, and the exchanges I written for them had such a keen sense of verisimilitude that I couldn’t help but feel proud of myself. Every person that I showed my early drafts to all reflected my feelings towards the two of them. It’s not that they were in love with each other, that much was obvious, but it’s that they weren’t afraid to argue with one another, knowing full well that what they said would be resolved in due time. They truly felt like two, real people who were in a committed and loving relationship.

Laurel, on the other hand, I liked for a completely different and darker reason. If one remembers correctly, Laurel was the girl who had succumbed to a crippling heroin addiction; not something typically associated with the cheeriness and wholesomeness of married life. It was no coincidence that I paired her chapters right next to Sergio’s; while one character was living a hell on Earth, the other probably couldn’t be happier. It would be cruel, if these were real people we were talking about here.

Writing Laurel’s chapters, I felt an odd mixture of pride for having written what I considered my best work yet, and disdain for what I was putting Laurel through. Her very first chapter involved her waking up in her sticky, broken down house in Inglewood, and quickly becoming overcome with what junkies call, “itchy blood.” She had scratched nearly every surface on her body, letting blood and leaving scars wherever her nails had dragged. The chapter ended with her on the bed, screaming in pain and half out of her mind. She would wake up later in the story, being visited by a junkie looking for some smack that she would be willing to sell him.

I had planned Laurel’s story to be one of redemption. Through the course of the story, she would hit rock bottom, and crawl her way through The Hero’s Journey, and on the path that led out of the dark world that she lived in. She wouldn’t kick her habit, or at least, the story would never explicitly state that, but the reader would have every reason to believe that she would be alright in the end.

At least, if the story were ever finished.

The inevitable happened. Projects began piling up, I lost interest, I began to doubt my talents as a writer, the usual garden variety of reasons. To this day, Normandie remains incomplete.

It’s silly, but I do feel a bit bad about leaving the characters where they were, both physically and mentally. There would be no epiphany for Marcus, Matthew will remain a simpleton and little else, and Laurel will always be trapped in that ramshackle house, either on junk or in torturous agony. Well, at least until I feel that spark again.